Danish Video cover

READ ANOTHER REVIEW OF THIS FILM HERE!

Danish Video cover |

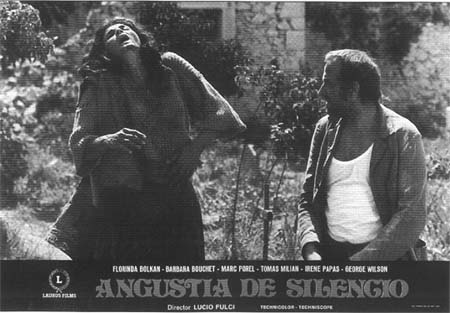

DON'T

TORTURE A DUCKLING

DON'T

TORTURE A DUCKLING  |

Tomas Milian and Barbara Bouchet |

Both films revolve around protracted scenes of interrogation

and share several key points of common imagery, from their title sequences of

bare hands revealing safeguarded objects (accompanied by a melancholy, half-heard

vocal) to the unsettling effect of a woman's voice raised in shrill accusation

in a public meeting place; the Maycomb County oak tree where Robert

Duvall's mentally deficient Boo Radley leaves the gift of soap dolls anticipates

both Accendura's "oak by the crucifix" (where the lifeless body of

one victim is left) and the wax effigies molded by Florinda Bolkan's feral Maciara.

While both stories lay their action in Southern communities resistant to social

change, DON'T TORTURE A DUCKLING is no more a simple condemnation of

rustic intolerance (as has been argued) than TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD intended

to localize America's race problem below the Mason-Dixon line.

George Wilson as the hermit OLD FRANCESCO |

|

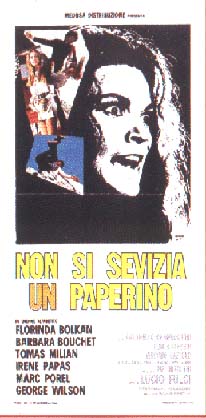

Inverting the narrative arc of TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (its climactic forest pursuit is pushed ahead here to serve as DUCKLING's first suspense setpiece) and eliminating his trio of child protagonists early on, Fulci dashes the inherent hope of the Mulligan film (an adaptation of the novel by Harper Lee). By backgrounding the murders, making them a grim inevitability in the fractious climate of his fictional Accendura, Fulci reveals himself to be interested less in blaming institutions (the Catholic church, the government, the media) than in identifying the cultural conflicts that sire such aberrations. DUCKLING's screenplay, by Fulci and frequent collaborators Gianfranco Clerici and Roberto Gianviti, locates true evil at the end of a skein of thwarted human communication that twists through the oral tradition from mysticism and magic to the call and response of the Catholic mass straight on to local gossip and the popular fascination with tabloid journalism. If blame must be assigned, Fulci seems to suggest, then blame must be shared by all who obscure the truth through language: from the faceless killer of children to Tomas Milian's unscrupulous journalist (who withholds evidence from the authorities to follow his own leads and redresses crime scenes "for that macabre touch"), to Barbara Bouchet's junkie heiress (whose predilection for young boys betrays an inability to communicate with adults) to the village priest (Marc Porel) who controls what magazines are read by his parishioners, to the carabinieri who seem more interested in advancing their pet theories than in protecting the innocent.

Florinda Bolkan as the "witch" Maciara |

Regardless of the clash of cultures, faiths and personalities at the heart of DON'T TORTURE A DUCKLING, it's all one in Accendura: the gossip muttered around the village washtub (it's no surprise that one victim's body is dumped where the citizenry airs its dirty laundry) proves a source for the news dispatches of the giornalisti, which are telephoned out over the same lines that carry extortion demands and the anonymous accusation pointing suspicion at Maciara for the murders of the village's "dirty boys. (Fulci has his cast spend so much time on the telephone-- an appliance loaded with more significance in Italian cinema than of any other country-- that one suspects a partial inspiration in BYE BYE BIRDIE!) Even Maciara's bitter curses are little more than a crude articulation of the ill will that is Accendura's mother tongue, itself emblematic of a wider societal disregard that encourages stereotyping and goes a long way towards explaining the "social death" behind the smoke and mirrors of Haitian voodoo. The failure of these characters, whether rural or urban, to breach cultural barriers and communicate honestly with one another (the film's most impassioned relationships are between the victims and their killer) urges the suggestion that psychopaths are made, not born. The arbitrariness of evil is beautifully communicated in Maciara's interrogation by the police; asked who she thinks "the devils" have chosen to carry out the murders demanded by her maledictions, Maciara's response is as chilling as it is inevitable: "Anybody." Rather than targeting institutional hypocrisy or aberrant psychopathy, DON'T TORTURE A DUCKLING sets its critical sights on the very human estrangement that breeds monsters.

Tomas Milian and Barbara Bouchet |

No mere anti-Catholic polemic, DON'T TORTURE A DUCKLING is an unflinching and an expressly catholic (by definition, "universal, broad in sympathy") morality play that requires its sinners to pay heavily for their sins: the intense jealousy of Dona Avallone (Irene Papas), which has driven her husband to an early grave, turns back to afflict her own offspring with retardation, while Barbara Bouchet's sexually teasing Miss Patrizia is humiliated before a phalanx of adult men. Although the brutal chain whipping of Maciara is often read as Fulci's condemnation of gang mentality, it can also be argued that the vindictive recluse has brought her fate upon herself, heedless as she has been to the calculus of black magic which repays a dark curse ("I'll break you!") four-fold. By positing a world in which people suffer the direct consequences of their own words, DON'T TORTURE A DUCKLING transcends glib finger-pointing to speak truth to a culture unbalanced by having one foot planted in an ancient world of saints and martyrs while the other is set in a modern age of lonely people without a vocabulary to express their sadness. The film's opening image of hands tearing at the earth to deliver up the brittle bones of a stillborn child stands in testimony against a society mooting its own prospects (a sentiment echoed in a snatch of overheard soap opera dialogue that asks "What possible future is there for us?").

The brutal chain-whipping scene. |

|

Viewers more familiar with Fulci's later full blown (and

often bullying) explorations of horror will be astonished by the director's

patience and control of the material here. Although Fulci and director of photography

Sergio d'Offizi (CANNIBAL HOLOCAUST) employ a number of aggressive cinematic

devices (deep focus, extreme close-ups, off-kilter camera angles and inspired

use of the zoom lens), these never upstage the story's human element. More impressive

is Fulci's use of visual doubling to underscore his central theme of the sameness

of perceived opposites: as the local boys fabricate fleshy embodiments ("huge

tits like watermelons and huge rears") to satisfy their sexual curiosity,

so Maciara forms effigies of them to channel her resentment at the life denied

her unborn son; using black-headed pins to pierce her voodoo fetishes, Maciara

is ultimately delivered up into a piazza peopled by elderly widows who pass

a judgment that is silent but for the clicking of their knitting needles. (Extending

the piercing metaphor, Fulci presages the vigilante attack on Maciara by having

one of the village men raise the antennae on his car bonnet.) But none of these

scenes pack quite the emotional punch as the moment that finds Don Alberto genuflecting

in prayer over the unearthed corpse of the first murdered boy, while photographers

drop to their knees around him to snap pictures. (So masterful is Fulci's command

of the medium that he even uses the Italian intermezzo to support his leitmotif

of doubling.) Fulci would return to many of these themes (a sensationalizing

media, mob violence, children in peril, social bigotry) in subsequent films,

but he would never again be as forceful or as fair.

--Richard Harland Smith

(This review was originally printed in a slightly different form in VIDEO WATCHDOG #64, and appears here via the courtesy of Tim and Donna Lucas, and the author, Richard Harland Smith.)

Irene Papas. |

Florinda Bolkan receives a chain-whipping by the local villagers. |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|